This is the first part of a two-part feature about the intersection of agriculture, business and culture at a place called the Corn Palace in the southeast corner of South Dakota.

Plenty of people happen upon the World’s Only Corn Palace while traveling through South Dakota, perhaps on their way to Badlands National Park or Mount Rushmore. Or the annual Sturgis megamotorcycle rally. Not so many make a pilgrimage for the sole purpose of gazing at a 19th century public monument dedicated to agriculture featuring mosaics fashioned almost entirely out of corn cobs and stalks. I’ve visited the Corn Palace a dozen times over the years, but never with a serious interest in making sense of its 130-year presence on the northern Great Plains.

I admit it. It’s impossible not to feel a certain smirk factor here. In our jaded time, there is something, well, corny about huge mosaics made from corn on the cob. And yet the Corn Palace is in some way irresistible and the mosaics — believe it or not — are not just good folk art but sometimes an admittedly unusual kind of fine art. One of South Dakota’s most distinguished visual artists, Oscar Howe, a Native American of the Yanktonai Dakota tribe, produced some of the most remarkable permanent corn mosaics on the interior walls of the palace.

In a more innocent age, when homestead states were doing everything in their power to lure new immigrants to their lands, there were 34 corn palaces in the Midwest, a couple of them proximity rivals to the Corn Palace in Mitchell. In the frontier railroad days, the Northern Pacific and the Milwaukee Road, among others, put on marketing fairs in the U.S. and Europe featuring a 250-pound pumpkin or a zucchini the size of a Civil War cannon. They promised a new Eden in what turned out to be hardscrabble farms on a semi-arid landscape in the middle of nowhere.

My Pilgrimage to the Mecca of Maize

My GPS informed me that it was approximately 375 miles from Bismarck, N.D., where I live, to Mitchell, S.D.

When I can, I prefer to drive the back roads. You are closer to nature on those old narrow blacktops and you can stop on a dime, whereas on the freeways you just zip by. Besides, I wanted to observe the Dakota grain elevators and see if I could get a sense of the magnitude of this year’s corn storage.

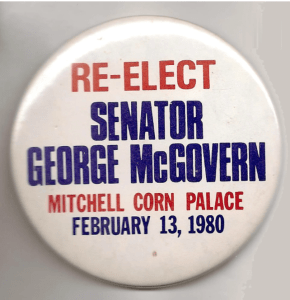

I drove south of Sterling, N.D., to the South Dakota line, then turned east towards Aberdeen, and finally on a zany zig-zag trajectory on farm-to-market roads to Mitchell, population 15,660, the seat of Davison County, and the boyhood home of one of my heroes, former U.S. Senator George McGovern. The terrain through which I drove would be described by the untrained eye as “flat” or “monotonous” or even “dreary,” especially in winter. But I find the plains beautiful and compelling. An acquired taste perhaps.

The Dakotas have historically been hard red spring wheat country (King Wheat), but the ingenuity of genetically modified crops have in recent decades permitted corn, soybeans and sunflowers to extend their territorial reach west onto land that in 1960 would only support small grains. As I drove south and east toward moister places and longer growing seasons, each county I rolled through produced more corn than the last.

A Brief History of Commerce on the Cob

Corn is one of the Western Hemisphere’s gifts to the world. Zea Mays was first domesticated by indigenous people of southern Mexico perhaps 10,000 years ago. We have all been taught that the Patuxet Native American Squanto had to teach the Pilgrims how to grow maize in a landscape so little understood that they named it New England. Some historians say that if the Native Americans had not introduced European settlers to corn, more would have starved, and the first waves of English colonization would have failed miserably. Later, when Lewis and Clark reached the Mandan and Hidatsa earth lodge villages in late October 1804, they encountered Native American master farmers who had created nine (some say 13) distinct varieties of corn and stored it in elaborate underground silos. To get through a hard winter in North Dakota, Lewis and Clark fashioned metal implements and weapons for the Mandan in exchange for boatloads of corn.

When master gardener Oscar Will developed his extraordinary Pioneer Brand Seed Co. and catalog in the first years of the 20th century in North Dakota, he distributed Mandan and Hidatsa seeds nationwide. His catalog covers were beautiful tributes to Mandan gardeners.

South Dakota produces a lot of corn: 740 million bushels per year. Even so, South Dakota only ranks sixth in U.S. corn production after Iowa, Illinois, Nebraska, Minnesota and Indiana. Iowa produces a whopping 2.5 billion bushels of corn per year. In fact, Iowa is so corn-fertile that if it were a separate country it would rank fourth in world corn production: USA first at 14 billion bushels per year, China at 10 billion and Brazil at 4.8 billion.

At least four times on my daylong drive, I stopped at a random giant steel grain elevator complex. They were all deserted on a Sunday afternoon. Every one consisted of two, three or four huge steel grain bins, each containing about the same amount of corn as a major league football stadium could hold. But that was merely the indoor storage. Each one also had one or two gigantic pyramids of bright yellow corn kernels sitting out the Dakota winter. There is so much corn surplus that it cannot all be stored inside.

At least four times on my daylong drive, I stopped at a random giant steel grain elevator complex. They were all deserted on a Sunday afternoon. Every one consisted of two, three or four huge steel grain bins, each containing about the same amount of corn as a major league football stadium could hold. But that was merely the indoor storage. Each one also had one or two gigantic pyramids of bright yellow corn kernels sitting out the Dakota winter. There is so much corn surplus that it cannot all be stored inside.

The corn pyramid is usually buttressed at the surface level with peripheral concrete abutments to keep it from spreading out. Some are covered with immense white plastic tarps the size of a Walmart. Each of these vast corn storage facilities has a huge drying apparatus, each burning vast amounts of natural gas. It’s essential to keep the corn from absorbing too much moisture.

In a certain sense, these corn storage facilities are more impressive than the World’s Only Corn Palace. In many Great Plains and Midwestern towns they are the highest building for a hundred miles. Built at vast expense, each one handles more corn than the whole state of South Dakota would have produced back in 1917. The goal of the keepers of this corn mountain is to get it all sold off before next year’s superabundance shows up. Parked along the edge of the concrete lot were a half dozen 18-wheel tractor trailers, waiting to be filled with corn for delivery to, well, probably beef feedlots farther south, or ethanol plants in the region.

If Americans Don’t Eat Much Corn, What Good Is It?

If America stands for abundance, you see it here in its most basic macrobiotic form. You cannot help but be impressed. And since the American people only dine on 1 percent of the nation’s corn supply as corn on the cob or creamed corn, you find yourself standing under the corn mountains and wondering, where the heck does it go and what do we do with all of it?

There are ready answers to these questions.

On the three occasions when I filled up my car with gas on my pilgrimage, I made sure to choose 10 percent ethanol. That means that 90 percent of that fuel came from oil and 10 percent came from corn (via oil). The Trump administration attempted to raise that quantum to 15 percent nationwide to support the ethanol industry, a 2016 campaign promise, but in 2021, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia struck down the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) initiative.

The Defining Cornscape of Mitchell

I arrived in Mitchell at about 5:45 p.m. just as the winter sun was sinking over the southwestern horizon. I was weary from a long day on the road, eager to check into my hotel, get some dinner, and prepare to meet the executive director of the Corn Palace first thing the next morning. But I found my car almost mystically funneled right through downtown Mitchell where, before I was quite ready, I saw the palace’s onion domes and the minarets and, of course, the giant corn mosaics.

The Corn Palace has been built and rebuilt several times since its inception in 1892, but it has always featured a strange medley of architectural styles and ornaments. In fact, the most recent iteration is decidedly more modest than the Rococo bombast of earlier decades, when the Corn Palace roof was a blizzard of domes, fillagree, cupulas, minarets, and other mismatched ornamentation.

The Corn Palace was serene at dusk on a Sunday in early March, one of the quietest months on the northern Plains. The winter sunset cast a roseate glow over the three metal onion domes atop the Corn Palace, which I was later informed, with some emphasis, have nothing to do with Islam, Communism, or Eastern Orthodox Christianity. I got out of my car to stand athwart the main façade of the Corn Palace — and gaze. My pilgrimage had been long and not without its challenges, but I had reached my destination in front of a thing unique in a world of 195 countries and 7.7 billion people.

I couldn’t decide if I were a Jeffersonian pilgrim bowing before a heartland Temple to Demeter or Clark Griswold misting up somewhere between Wall Drug and the World’s Largest Ball of Twine. The Corn Palace is both unusual (odd, really) and very beautiful, far more artistically accomplished than kitschy. As I stood stretching my numb legs, I could almost hear a muted version of the opening of the film “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

I had arrived. I felt like a friend to corn. I felt respectful heritage ties to the extraordinary 19th century immigrants who had the gumption to prove up their homesteads in so remote a landscape. My grandparents were among them. I can remember the wonderful pungency (almost intoxication) of the silage in the concrete corn silo on the farm. Each year, Diedrich and Rhoda Straus planted a couple of rows of sweet corn at the edge of a large field of feed corn. We’d drive out in the old 1957 IH red pickup and snap off a couple dozen ears for a Sunday family harvest feast.

The World’s Only Corn Palace raised all sorts of questions as I gazed on it alone in the heart of Mitchell, but it did not disappoint. I was proud to be a Dakotan, even if from the wrong one. It glowed with fertility as dusk came to the Great Plains.

Burning Seed Corn as Fuel

America raises 91.7 million acres of corn. That’s an area about the size of Montana and a little smaller than California. Approximately a third of America’s corn is burned in automobiles by way of ethanol. A second third is fed to cattle and hogs on their way to becoming beef and pork, and to chickens and even salmon. The final third has a wide range of miscellaneous uses. Some is consumed by humans in cereals, soft drinks, breadings and other food products. Some is used in a breathtaking number of non-food applications.

And some is exported. Americans are not great eaters of corn, at least until it has been processed beyond recognition. Most of the corn we eat comes in the form of food additives and high fructose corn syrup (HFCS). According to recent studies, Americans consume 10 percent of all of their calories from HFCS, which is so cheap to produce that the fast-food industry pushes large servings, which have helped to raise the national obesity rate in the United States to 36.2 percent. The cane versus corn sugar debate is complicated, controversial, and a bit tedious, but the consensus seems to be that we’d be better off consuming our sugar from cane or even sugar beets than from HFCS. In this, as in other American food consumption habits, what we ingest has more to do with price than with optimal health.

Yellow-Eared Persistence

Why has the Corn Palace in Mitchell survived when all its 33 rivals have disappeared, most of them 80 or more years ago? Three reasons, says Corn Palace Director Doug Greenway, who sat for an interview with me at the free throw line of the Corn Palace basketball court: It’s now unique not just in the United States but in the world, which gives it special bragging rights and tourism cache. The people of Mitchell, including the Chamber of Commerce and the city government, have embraced the palace, says Greenway, and supported it through good times and bad. And the Corn Palace is a multi-use municipal facility so that corn is not the only draw. In fact, Greenway said that the tens of thousands who attend the 150-plus high school and college basketball games per year held on the floor of the Corn Palace get nonchalant about the corn mosaics that grace the walls on three sides of the basketball court. “They come to see the game not the corn art.”

Why has the Corn Palace in Mitchell survived when all its 33 rivals have disappeared, most of them 80 or more years ago? Three reasons, says Corn Palace Director Doug Greenway, who sat for an interview with me at the free throw line of the Corn Palace basketball court: It’s now unique not just in the United States but in the world, which gives it special bragging rights and tourism cache. The people of Mitchell, including the Chamber of Commerce and the city government, have embraced the palace, says Greenway, and supported it through good times and bad. And the Corn Palace is a multi-use municipal facility so that corn is not the only draw. In fact, Greenway said that the tens of thousands who attend the 150-plus high school and college basketball games per year held on the floor of the Corn Palace get nonchalant about the corn mosaics that grace the walls on three sides of the basketball court. “They come to see the game not the corn art.”

To get ready for my journey I reread one of my favorite books, Michael Pollan’s “The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals,” first published in 2006. It’s an important book, clever and well-written. “The Omnivore’s Dilemma” followed his earlier classic “Botany of Desire: A Plant’s Eye View of the World” (2001), which is how I got hooked on Pollan. (Some agriproducers say they are allergic to Pollan!)

Pollan’s thesis in the “Omnivore’s Dilemma” is simple. We produce way too much corn. Because of its large biomass (compare a full-grown corn stalk to a stalk of wheat or oats), corn requires a lot of inputs: water, fertilizer, pesticides, herbicides and diesel to run the giant equipment. Because corn takes a lot out of the soil, you have to put petrochemical products back in to sustain that level of multiyear monoculture. The necessary chemicals (including the diesel burned by tractors and combines) are not good for the planet’s carbon footprint, not to mention the health of the soil or the groundwater where excess nitrates wind up.

For many decades we have grown so much corn that the price is constantly in jeopardy of collapse. To take up the huge surplus, we’ve had to invent a bunch of irrational uses for corn: the high fructose corn syrup that now sweetens 65 percent of America’s soft drinks; fattening up America’s beef herds with a grain they (as grass foragers) have a hard time digesting; and the alchemical transformation of corn into ethanol to fuel American automobiles. The corn industry will happily declare that engineers have invented more than 4,000 uses for corn in applications you would never suspect: varnish, hand soap, wax paper, crayons, coated aspirin, diapers, paving bricks and gypsum drywall, along with 3,992 other products, some of them food.

Pollan’s view is that a kind of national corn mania has sprung up since World War II that makes corn the most abundant crop grown in the United States. Good news and bad news, for Pollan mostly bad. With clever accounting, the powerful farm lobby and a willing and complicit U.S. Department of Agriculture, growing so much corn can be made to seem like a reasonable thing to do. But if you care about the planet or the health of the cattle, hogs and chickens you buy at the grocery store, or your own health for that matter, not to mention food justice in a hungry world, you might want to rethink the American corn equation.

Cannot Blame the Corn Palace

That’s not the spirit of the World’s Only Corn Palace, of course. It would be unfair to ask the Corn Palace to be anything other than a fascinating roadside attraction and a lingering monument to the role that family agriculture played in the frontier life of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Corn Palace hosts neither annual National Corn Growers Association conferences nor apocalyptic meetings organized by the Jeremiahs of the global climate change debate. The Corn Palace is innocently nonpolitical. The Corn Palace is not interested in the great corn debate.

You can also hear more of Clay Jenkinson’s views on American history and the humanities on his long-running nationally syndicated public radio program and podcast, “The Thomas Jefferson Hour,” and the Governing podcast, “Listening to America.” Clay’s most recent book, “The Language of Cottonwoods: Essays on the Future of North Dakota,” is available through Amazon, Barnes and Noble and your local independent book seller. Clay welcomes your comments and critiques of his essays and interviews. You can reach him directly by writing cjenkinson@governing.com or tweeting @ClayJenkinson.