One of Dad’s tasks as autumn hummed into winter was lifting his golf clubs from the car trunk and storing them in the basement. He was doing this one October when I was about 16.

“Why’d you ever come back to Minnesota from San Diego after the war?” I asked. “You could play golf all year.”

Fate had made the bullets miss when the Japanese shot at him on land, sea and air. You’d think it would change a man.

“I thought about it,” he said. “If I had stayed there, I’d never have met your mother and you wouldn’t be here.”

I said, “I’d be here in some form. And I’d be in San Diego.”

Ted Williams came from San Diego, where they played baseball all year. Williams spent his career in Boston and was devoted to the Jimmy Fund, which raised money for kids with cancer. He came from a hard childhood, survived combat in two wars and appreciated how the ball can bounce on life’s Roulette wheel.

“It’s only a freak of fate, isn’t it,” he said, “that one of those kids isn’t going to grow up to be an athlete and I wasn’t the one who had cancer.”

Ah, fate.

Dad was so cool he made Sinatra look like Wally Cox. Yet he entered the picture only because Mom’s first husband died in 1945. A small slice of Americans were making their push to Hitler’s Haus on February 23. The 102nd infantry crossed the Roer River that snakes through Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands. Bob Dreier didn’t make it. He would be 100 this year and saw a quarter of that.

Mom’s first husband seemed a footnote in our household. I watched World War II TV shows in the 1960s, had toy soldiers and guns. It wasn’t until I was in my 40s that it occurred to me that Mom could have forbidden it all. But for her, my fun had been more important than her grief.

Mom sometimes mentioned how the Germans had opened a dike to turn the river into a whitewater rafting, shooting gallery experience from hell. Weighed by equipment and ammunition, Bob drowned.

We lived in a city where the rivers forked. I knew rivers. How was this possible?

The Bois de Sioux runs between Minnesota and North Dakota. The golf course where Dad played before a gallery of mosquitoes is the only course in the nation with the front and back nines in different states.

In the 1960s, hackers wobbled from one nine to the other on a swaying pontoon bridge over the Bois de Sioux. It was maybe 40 yards.

That’s the river I envisioned Bob crossing. How could you drown in that? Vic Morrow and Rick Jason would have made it in the TV show “Combat!” that Mom dutifully watched with me.

I later learned the shuddering details that Mom never knew from men like Dick Skene, whose name was written on the back of a black-and-white photo of Bob taken shortly before his death at the German front.

On the back of the photo, Bob wrote, “Latrine duty,” then, as if to spark his own memory when he returned to the States, he had penciled, “Skene. Veit. Rackie. Tidy, who turned out to be a guy named Tideback.

Yup. With the Internet and some time, you can identify a man with a nickname in a 1945 photo.

I found Dick Skene after Mom died. Four of us planned a trip to Paris and London. I told my wife that we should split from them after Paris and head to Margraten, Holland, where Bob rests in a national military cemetery.

In Margraten, every American grave is adopted by a local, and every Memorial Day they flock to a ceremony there.

I asked innkeeper Jan why, after well over a half-century, locals still hold dear those buried in the rich Dutch farmland that was surrendered for an American cemetery.

“Because you saved us,” he said. “Otherwise, we would be speaking German. Or Russian.”

“I didn’t save anyone,” I thought.

Indeed, it wasn’t Americans who saved them. It was a scant few Americans, like Bob, who with his new wife was working for Lockheed in his home state of California when it was decided that Hitler needed a slap upside the head.

War correspondent Ernie Pyle — like so many journalists a war fatality — was well aware who did the heavy lifting when he wrote, “All the war of the world has seemed to be borne by the few thousand front-line soldiers … destined merely by chance to suffer and die for the rest of us.”

Dick Skene expected death. Like “Tidy,” the Internet had found him and other survivors of the 102nd infantry.

Skene told me on the phone that he thought himself to be a better than average swimmer. When the boats he and Bob Dreier were in capsized in the cold, swift Roar, he needed all of that experience. And a good knife.

Skene’s helmet came off and rushed way. He went under, hit the bottom of the riverbed and bounced back for air. He went down again, came up, went down, found his hunting knife and before exhaustion won, he cut the bandoliers of ammunition from his back.

A life preserver shot by. He grabbed it. Another GI struggling in the icy river came near. Skene snagged him. They reached a bend in the river and grabbed a branch.

The old swimmer said his memory was starting to fail him when we talked. But he had written, “I don’t know whether the ones who were missing were killed by enemy fire or drowned in the river. Our history book says there were no drownings, but I seriously doubt that. At any rate, John Stivali was missing. Bob Dreier was missing.”

Over the years, I rebuilt more of Bob’s final days than Mom would want to know. The scene I once envisioned of some guys who couldn’t get across a river to the back nine now belonged in a movie.

There’s a grave marker somewhere in North Dakota for Bob. His parents put it there. Mom got to make the call on where Bob would stay. She left Bob in that stunning military cemetery, which beats the hell out of a gravestone on the prairie.

The woman who adopted Bob’s grave, a European military veteran, said, “Your mother made the right decision to leave Robert with his comrades.”

If Bob had come home alive, some form of me would not have grown up with Dad in my alternative home town of San Diego. I would have been with Mom in L.A.

They play baseball all year long there, too.

If Ted Williams understood that he could have been a kid with cancer instead of the greatest hitter who ever lived, what the hell: Bob had good size. He was a 6-footer. I assume he could throw a baseball.

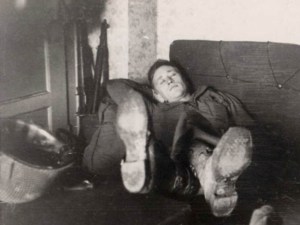

In my favorite, overexposed photo of him, he’s pretzeled into a chair, reading. He looks flexible.

If that Roulette wheel had played differently, I’d have grown up in L.A. And I sure as hell wouldn’t want the marble to fall in a slot that led to a career at Lockheed.

I’d be a retired big-league baseball player. And I’d be in the Hall of Fame.

One thought on “JIM THIELMAN: Fate — Life’s Tricky Pal”

Tom Coyne February 26, 2019 at 5:22 pm

Great piece, Jim. At 66, this really hit home with me. Thankful for the way life played out.