Doc Kippen looked down at me through black-rimmed glasses, bows disappearing into his gray hair at the temples. “I wish I had a bullet for you to bite on, Jimmy.” I was on my right side, left foot pulsing with each heartbeat as the ankle hovered above my left hip. It could have been someone else’s leg. I had no control over it.

I was on the X-ray table. Film of my fractured femur was on the wall. The room featured only hard surfaces to amplify a world-class scream from a 9-year-old when Doc Kippen pulled my left foot down to its home.

The percussions of that yelp would have bounced into the waiting room and sparked patients to shove aside wheel chair-bound folks, pregnant women and nurses in a rush to the door if this had been a comedy film.

Worst year ever? Headlines keep teasing that question about 2020. Maybe. But I never made the mistake of being 9 again.

COVID stories refer to pandemic deaths, then focus on the living, who make a better audience. We’re fatigued, isolated, miss our co-workers, classmates and sitting at the bar behind a hill of pull tabs.

Will COVID revisit survivors in 25 years, similar to shingles, which can appear decades later in chicken pox victims? Experts don’t know, unlike Doc Kippen, who knew that I’d limp for the rest of my life if he put me in a cast. He prescribed a daunting alternative: three weeks in traction.

My address was an east-facing room in St. Francis Hospital, which sat smack dab where the Otter Tail and Red rivers meet, so far west in Minnesota that if you lobbed a baseball from that hospital roof you’d hit North Dakota.

The January sun peaked over the lip of the sky early in that room, just before a nurse appeared with a wash rag and a bed pan. Days were long.

My best pal brought my school assignments to Mom, who relayed them to me. My fourth-grade teacher appeared a couple of times a week to shatter boredom that featured no Internet, three TV channels with endless daytime soap opera programming and rare visits from friends. Nine-year-olds don’t drive. My days were filled with adults.

Mental health? I was my usually own teacher. I scheduled no lectures, so a day’s school work took 90 minutes. I read anything I could, except that Bible in the bedside drawer. The place was filthy with enough nuns to satisfy a young Episcopalian’s spiritual needs.

Three weeks passed. Just as COVID was forecast to die in warmer weather, another X-ray was forecast to trigger my discharge. It triggered three more weeks without my dog, followed by six weeks at home playing Jimmy Stewart in “Rear Window.”

People ask how I fractured my femur walking home for lunch in fourth grade. “We lived in a rough neighborhood,” I say. They don’t need details. Their minds churn stories, all of which are probably better than the truth.

Which is rather how, “based on a true story,” it came to be that a kid of German heritage overcame the worst leg fracture ever to become a world-renown member of a Chinese dance troupe.

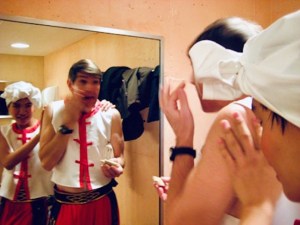

It’s largely unknown that there is a disturbing shortage of Chinese men who want to participate in annual Chinese dance performances at large venues in St. Paul. There’s also a sucker born every minute. My friend, Grant and I renewed our memberships a few years back when someone asked if we would like to be in a Chinese dance performance.

We spent hours a week practicing Chinese dance. We scoffed when friends assumed that we were incompetent. We were monumentally and multiculturally incompetent. This didn’t prevent us from lying about our skills and concocting a story about a 9-year-old kid, traumatically scarred by a devastating childhood injury who rose phoenix-like to become one of the world’s foremost Chinese dancers, a lithe man who leapt onto the stage to the thunderous applause of growing legions of Chinese dance aficionados.

The fable grew with each telling. Then came the day a sea of 8-year-old girls appeared before us at the first dress rehearsal. It became evident that they were to carry the performance. Our role was to provide a breather between numbers. We were the infantry, taking casualties until the fly boys winged over to save the day.

These talented, prancing angels had not seen us sweat and stumble, Frankenstein-like, through two-hour practices. They first laid eyes on us at dress rehearsal with horror, dismay, humor and contagious pity.

Rather than slink from this, Grant looked down at the girls, all colorfully, beautifully and impeccably attired. “I’m the prettiest,” Grant announced. “Right? Who’s the prettiest here? It’s me, right?”

The withering scoffs made me want to limp in circles as I told the soul-crushing story of my ninth year on earth, but to what point? This was an unflinching, intolerant group. I pitied their future husbands.

Those girls are older now, living in a COVID world. If just one of them brushes aside her friends’ complaints of masks, isolation, no dance performances, and says, “You think 2020 is bad? Let me tell you a story,” it was all worth it.